John Paul II’s pontificate left an unparalleled legacy of papal teachings. One key aspect of his tenure is the space he created for the work of other great theologians. The new pope, Benedict XVI, formerly Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, is one of them. Given Ratzinger’s sharp focus on doctrine, many have seen only one side of this man: the protector of the faith, the leader of a new „inquisition.” Few have focused on his rich analyses of freedom.

Just over two decades ago, Ratzinger’s office published a strong indictment of certain aspects of „Liberation” theology. This document dealt a huge blow to the most radical elements of the Church, a blow was compounded by the collapse of the Soviet atheistic utopia. John Paul II and Vatican theologians then focused on another enemy which affected East and West alike: the tyranny of relativism.

In his Encyclical Veritatis Splendor, the late Pope argued that the current culture „generates skepticism in relation to the very foundations of knowledge and ethics, and . . . makes it increasingly difficult to grasp clearly the meaning of what man is, the meaning of his rights and his duties.” His goal was to provide the compass for the practice of virtue as the first step needed for a moral recovery of civilization.

Classical liberal and „moderate” intellectuals were concerned that after the forceful defense of objective truth in Veritatis Splendor, the Church would to revert to imposing this truth by promoting coercive legislation. Yet this wasn’t the case. At the time of the encyclical, the Pope visited Sudan, a largely Muslim country, and argued forcefully that majorities do not have the right to impose their religious and moral views on minorities. The Wanderer, one of the most conservative Catholic newspapers, editorialized in favor of the „libertarian” slant of the Vatican Sudan statements.

Cardinal Ratzinger focused on teaching the importance of convictions, rather than force. On November 6, 1992, at the ceremony where Ratzinger was inducted into the Academy of Moral and Political Sciences of the Institute of France, he explained that a free society can only subsist where people share basic moral convictions and high moral standards. He further argued that these convictions need not be „imposed or even arbitrarily defined by external coercion.”

Ratzinger found part of the answer in the work of Tocqueville. „Democracy in America has always made a strong impression on me,” the cardinal said. He added that to make possible, „an order of liberties in freedom lived in community, the great political thinker [Tocqueville] saw as an essential condition the fact that a basic moral conviction was alive in America, one which, nourished by Protestant Christianity, supplied the foundations for institutions and democratic mechanisms.”

In his work as a theologian, Benedict XVI places freedom at the core of his teachings. He has a beautiful way of explaining creation, which according to him should be understood not with the model of a craftsman, „but the creative mind, creative thinking.” The beginning of creation is a „creative freedom which creates further freedoms. To this extent one could very well describe Christianity as a philosophy of freedom.” Christianity explains a reality that „at the summit stands a freedom that thinks and, thinking, creates freedoms, thus making freedom the structural form of all being.” This freedom is embodied in the human person, the only „irreducible, infinity-related being. And here once again, it is the option for the primacy of freedom as against the primacy of some cosmic necessity or natural law.” Human freedom pushes Christianity away from idealism.

Benedict XVI argues that freedom, coupled with consciousness and love, comprise the essence of being. With freedom comes an incalculability — and thus the world can never be reduced to mathematical logic. In his view, where the particular is more important than the universal, „the person, the unique and unrepeatable, is at the same time the ultimate and highest thing. In such view of the world, the person is not just an individual; a reproduction arising from the diffusion of the idea into matter, but rather, precisely, a „person.”

According to Benedict XVI, the Greeks saw human beings as mere individuals, subject to the polis (city-state). Christianity, however, sees man as a person more than an individual. This passage from individual to the person is what led the change from antiquity to Christianity. Or, as the cardinal put it, „from Plato to faith.”

As a Roman Catholic, I and many others are already deeply grateful to Ratzinger and his teachings on creative freedom, that characteristic mark of the „infinity-related” human person. We can be sure that the newest pope will continue the legacy of John Paul II, placing freedom and dignity at the core of his teachings.

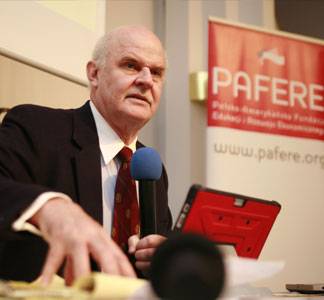

Alejandro A. Chafuen is an adjunct scholar at the Acton Institute for the Study of Religion & Liberty and the author of Faith and Liberty (2003, Lexington Books). Data dodania na starej stronie PAFERE : 2007-11-03 09:59:27